Discover more from Writing from Kate & Ali

📩 Letter #44: Giving back, giving up

Our mixed motives for doing good — and why they don't matter as much as we think.

Dear Ali,

In the last month, I’ve started delivering meals to homebound seniors and people with disabilities. Many clients can’t stand at the stove long enough to stir a pot, much less visit a grocery store. Volunteers pick up coolers packed with flash-frozen dinners — chicken fajitas, penne bolognese — and dairy items, either milk cartons or cheese sticks. Sometimes, they get packets of bread, or pears. One day, there were bonus burritos, donated in bulk by Meta, whose campus is in the same city as the distribution kitchen. “We have way too many,” said the coordinator, harried, as she threw a fragrant bag into my car. “You should eat one.” The tech company had offered abundance in response to scarcity. It was a well-meaning gesture, simultaneously too much and not enough.

Route sheets list addresses in nearby neighborhoods. I drive from location to location, listening to Christmas music on the radio, parking my car in precarious places. The route sheets lead me through finicky gates and narrow hallways, past holiday decorations and signs warning off solicitors. In the inner courtyards of an apartment complex, a man screams while a baby cries. I ring doorbells, and knock as hard as I can, hoping the clients will hear.

“Why did you start doing this?” a family member asked over Thanksgiving weekend as we sat by a fire eating chess pie. To combat poverty, I could have said. Many of these clients receive their meals as a government benefit. They live in mobile-home parks by the freeway and cramped apartments accessible only by slippery stairs. To serve the elderly, I might have replied. Some clients want to spend a little time together. We talk about the weather, and their pets. One woman told me that her location by the mobile-home dumpsters allowed her to strike up conversations with other residents taking out their trash. “What do I owe you?” another woman asked when I delivered her food. “Nothing,” I said. “Happy holidays,” I offer, lamely, as I leave.

The fire popped. I picked at my pie. “I’m sick of thinking about myself.” The relative chuckled. But the answer was an honest one.

I started volunteering not because I was feeling selfless, but because I was shocked at how selfish I’d become. Three hours, every two weeks, plus money for gas — this was my penance, the actual “least I could do.” Many stops come with notes. Client is blind. Client forgets to wear his hearing aids — knock loudly, and knock again. GIVE MEAL ONLY TO CLIENT: Client worries roommates will steal his food. The clients are often concerned that I will leave before they can manage to make it to the door. “I’m coming,” they cry, again and again. “I’m waiting,” I say. “Don’t worry.” Driving the route makes me sad, though the clients are often grateful, and there are some signs of care. A friend sits smoking on a porch. A grandson collects a meal for his grandfather. There’s also neglect — tangled flower beds, living rooms cluttered with papers. And there’s so much need. A man shyly asks if I’ll bring in a package from the driveway. His gratitude at the gesture makes me sick to my stomach. It’s really the actual least I can do.

The Bay Area’s inequity is almost a cliché. Multi-million-dollar fixer-uppers and growing encampments exist in the same neighborhoods. Those of us in the middle — confronted by both obscene wealth and awful poverty — complain about gas prices, groceries, child care, and rent, which really are burdens for most of the people who live here. We bemoan the inequality, but see no way of solving it. The situation paralyzes: Why do anything if we can only do so little? Delivering a few dinners twice a month doesn’t solve anything. So why do it at all?

Distributing the food does “put things in perspective.” When I drop off the empty coolers at the end of my shift, I drive home through the fog to my small, warm apartment. I mix cookie dough and put on soup. I call a friend. I walk around the block. I plug in the Christmas tree. I am reminded of how much I have. I am forced into gratitude.

But I don’t want to serve others just so I can feel better about my circumstances. I don’t want their situations to be a kind of consolation. At least that’s not me! How selfish. How dismissive. How cruel. Plus: I’m young. “Life happens,” so they say. These things, too — good knees, my memory, connections and consolations — can pass away.

In the meantime, I continue to strive for more even as I see those who have less. The week gets underway, and I am filled with desires. I think that’s true for many of us. We want more than we already have, even as we recognize that for many, what we have would be more than enough. This is especially true at Christmas, a season when we’re encouraged to give cans to the food bank, purchase a toy for a drive, or slip small bills into a red bucket. We’re congratulated for giving just a fraction. I often spend more on my family’s stocking stuffers than I do on acts of charity.

The uncomfortable truth: We want the poor to be cared for, but we also want to be rich. With such unsavory ethics, how can any of us actually be part of a solution?

Dig into your motivations for doing good and you’ll quickly find contradiction. (At least, I do!) There are noble reasons, yes: Compassion and empathy, religious conviction and moral grit. And lots of uneasy ones. I want to be the kind of person who volunteers. Good or bad? I want to live in a place where everyone is fed and has someone to talk about the weather with. I also want to buy a house, give my kids opportunities, go on vacations — and do what it takes to make that happen. Contradictory? Impossible? Immoral?

For now, I have to set these questions aside. If I don’t, they’ll keep me from doing anything at all. Really, I hope that by delivering these meals, I’ll decenter myself entirely — think less about what the process is doing to my own soul, whether I mean it or not, and more about the physical, literal impact it’s having on others. Rice and beans are warming in microwaves. Milk is building up someone’s bones. I want to think less about the origins of altruism and more about how altruism is at work now: even if my actions are barely significant, even if I’m not the best person to do them.

And I’m not. There are many delivery drivers on the routes, many people who donate more time and make better conversation. I’m always lost, and I can’t really parallel park. Last week, several stops in, I realized I’d neglected to give one client his frozen orange juice concentrate — his serving of fruit for the weekend. I returned to his apartment, knocked again, forced him to stand up and return to the door. “I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.”

The work of justice and care isn’t only mine to do, and it’s ridiculous to think that it could be. Best to just do something, and then hope for more, hope that the repetition will change my incentives. Hope that a few hours every few weeks will prepare me for bigger sacrifices and greater gifts. In the meantime, someone will have something to eat.

Love,

Kate

Searching for an organization to help fund this holiday season? Here are some of Ali and Kate’s favorite local nonprofits, located in places they’ve lived.

Second Harvest of Silicon Valley: Distributes food at over 900 sites across the region.

LiLY (Lifeforce in Later Years): Cares for elderly people living on the Upper West Side of New York.

The Father’s Heart Street Ministry: Serves people without housing in Clackamas County, Oregon.

Person to Person: Provides residents of Fairfield County, CT with food, clothing, and emergency financial assistance.

Central Texas Foodbank: Provided 54 million meals for Texans in need throughout 2020.

Inside Books Project: An Austin organization that sends free books to incarcerated prisoners throughout the state of Texas.

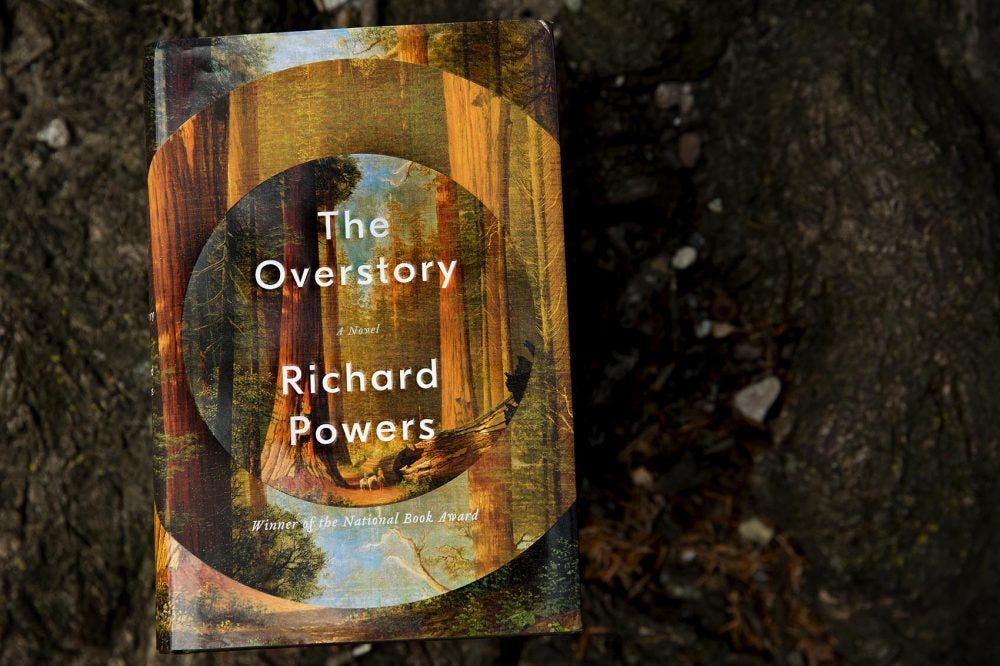

My book recommendation

I’m making my way through The Overstory, which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, little by little. Next week, over the Christmas holiday, I’ll be able to sit and read for hours at a time. It’s the kind of book that needs to be enjoyed that way, so lush with details and interconnections. So far, I’ve read its first two “interlocking fables” of immigrant families — Norwegian, Chinese — and their families — a chestnut, a mulberry. I’m moved by how Powers positions human frailty next to the lasting hope of ancestral memory and persistent nature.

Have any of you read The Overstory? Thoughts? (No spoilers!)

Happy holidays! We’re so thankful for your readership. Looking forward to sharing more books and ideas in 2022.

Subscribe to Writing from Kate & Ali

Links & excerpts from two writer friends, Kate Lucky & Ali Montag.

So beautifully written. Should be required reading for every American...

If everybody does a little, it adds up to a lot.

Thought provoking. Suggested book on this subject: The Epistle of James.