Discover more from Writing from Kate & Ali

Dear Kate,

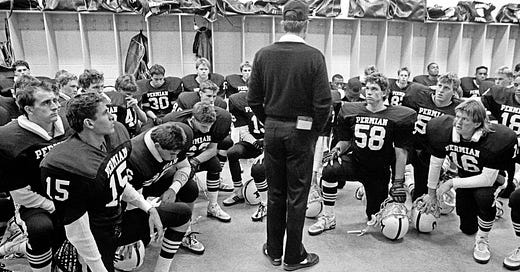

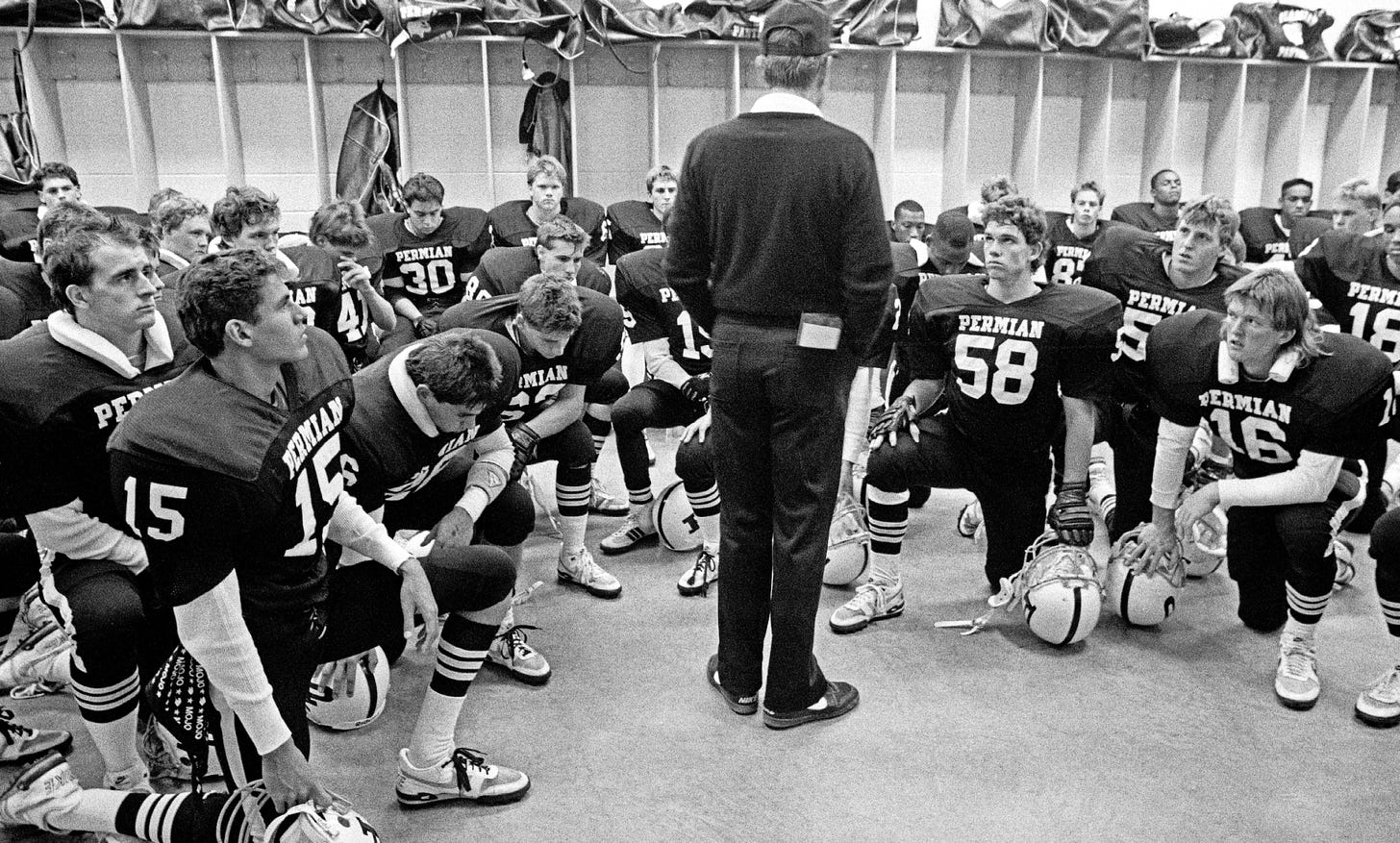

In 1972, banners covered the West Texas town of Odessa, black and white signs painted MOJO WINS. Neighbors held each other and cried. Fathers shook hands and slapped each other’s backs, grins spread wide. That year, their boys had done it: The Permian High School Panthers were state champions.

“We were hoarse from screaming and yelling. We didn’t want to leave the field,” quarterback Jerry Hix remembered years later, long after his high school football career had ended. “Nothing can compare. I miss it.”

Photo credit: Robert Clark, Friday Night Lives

It was a moment of indescribable pride for boys who spent the better part of their young lives cracking ribs, ripping tendons, and puking under the Texas sun, working toward a single goal: Excellence at the game of football. It was a moment of pride for the people of Odessa, the few thousand ranchers and oilmen and beauty clerks who scratched out lives in the arid desert, watching and praying over their team.

It was also a moment from which many of those boys would never recover.

“My life’s never been the same since,” said Joe Bob Bizzell, a player who flamed out of college football and retreated to the dirt roads of Odessa. A decade later, he found himself still there, repairing pump jacks on an Amoco oil field.

“You live in a fairy tale for that one year of your life,” said a different player’s wife. “You’re worshipped, and that year is over and you’re like anyone else. We all feel our husbands have been unhappier with everything they got out of it.”

Players fell into alcohol abuse and lackluster home lives. Permian High’s athletic trainer called winning a Texas high school football championship the “kiss of death” for teenage boys.

“They’re popular. They’re in very hot demand, like a hot rock group. No matter what they do, it’s a hit. Everything they do is right,” he said. “And they just can’t find that again. What other job can they find that has that glamour? What’s the substitute? Find the substitute for it. The only consequence of it is a mentally crippling disease for the rest of your life.”

Why am I recounting Pulitzer Prize winner H.G. Bissinger’s reporting in Friday Night Lights? First, because it is a wonderful book. Second, because as I’ve been re-reading it this week, the story feels uniquely relevant.

Bissinger’s nonfiction account of Odessa and its Permian Panthers isn’t just a book about winning football games. It’s a book about the lingering cost of life lived on a pedestal.

Flipping through Twitter last week, this video, “A day in the life of a New York fashion student,” popped into my feed. Watching, it wasn’t memories of NYC, or outfit envy, or nostalgia for my own youth that I first thought of (that came later)—but the boys of Permian High.

By all objective metrics, this girl is living a fabulous life. She’s beautiful, with nice friends, fantastic clothes, a fun gym routine, and professional success. Her video has been watched 4.1 million times on Twitter. Kate Bartlett has 421,600 followers and 16,300,000 likes on TikTok. That’s very real economic leverage. Employers will race to capture the power of a smart, appealing young woman.

She’s playing an expert level of the game as it is understood in 2021: Attract an audience. Curate your life. Optimize for beauty and likability. Be authentic, but careful. Precise. That’s how you win.

The rules of this game were written two decades ago—entirely unwittingly—by pale young men trying to get dates from a Harvard dorm room. In the firehose of faces, you needed a strategy to stand out. The ultimate rule was born: Be something special.

The pressure to be “special” is hard to quantify. It’s like an ever-expanding gas, taking the shape of every space it enters. The tools are available: There are guides for how to perfect your skincare routine. How to use several thin layers of spandex to eliminate any suggestion of cellulite. How to raise venture capital. How to achieve ketosis. How to make $1 million before you’re 30. How to achieve the perfect pouty lip. How to self-publish a book. How to burn 11,300 calories.

You can be a champion at anything. Therefore, you must be a champion at something.

Like football, champions are rewarded by a crowd of cheering fans. Fans are where the money comes from: Season tickets and popcorn sales and T-shirts and sponsorship deals. But that audience is no longer a West Texas town of 15,000 neighbors and cousins and friends: It’s billions of blinking eyeballs.

The game isn’t played in stadiums, but online. It is no longer bound by the friction of the physical world. There are no tryouts. There are no coaches. There is no 4-year time horizon. You cannot graduate from the gridiron of the Internet.

16,300,000 people have watched Kate Bartlett on TikTok. That is 162 different packed crowds at the Darrell K Royal Texas Memorial Stadium at the University of Texas.

16,300,000 people saw her as young and beautiful and smart and successful.

16,300,000 people will expect her to remain that way.

But if it is irreparably painful to live under the expectations of a crowd for one year—just one season of football—what must it be like to withstand that pressure for…forever?

Imagine yourself in college. Could you have handled that audience? My college days were spent blessedly offline. (This is because I was uncool, not because social media wasn’t popular.) I wore some bad outfits, ate mac & cheese on the floor, brought greasy sacks of McDonald’s into the library, said and did things that I regret. But the stakes were low. I could make mistakes and learn. No one held it against me if I goofed up. I could apologize, figure it out, and be better next time.

In front of 16,300,000 people, the stakes are high. Mistakes will not be tolerated. Cellulite will not be tolerated. In the game, you must be perfect.

Ringing endorsement of “content creators” is everywhere. TikTok is the future of celebrity. OnlyFans is the future of empowerment. Instagram and YouTube remain the keys to the golden castle. A loyal audience is a wellspring of power: cultural, political, or economic.

You and I are both writers—paid only for our words and ideas. We both make content every day. It pays the rent. I certainly value the dissemination of creative work, understand it to be an important tool, and believe it worthy of compensation and recognition.

But then I read about the torment a 17-year-old girl endures from 100 million strangers. I read about the eating disorder she’s hidden. I read about the violent threats in her DMs, pings that reach right into the palm of her hand. I listen to her cry. Can you watch this video without feeling sick? Can you really?

“She’s the most powerful influencer in the country! She has it all!” adults will tweet. “She has scale larger than some publicly traded companies! You shouldn’t feel bad for her.”

I think about these adults, strategizing about how to “leverage her brand.” They sit on Zoom calls. They make decks. I wonder if they get death threats.

I think about the systems these adults will build, and finance, and scale. I think about how these systems will impact everyone else, everyone who is not famous, but is now convinced that perhaps they could be. Should be.

I watch this video, a woman filming a dance for TikTok when a stranger appears inside her apartment. He has climbed onto the balcony. She shelters in a neighbor’s apartment until the video ends.

It’s easy to pretend the digital world is removed from the physical. It is not. I think about the millions of women streaming on OnlyFans. Are they safe? Then I think about myself. Have I tweeted anything that will reveal my home address? What have I posted? Who can find me? I feel sick.

I watch content, and I watch, and I watch, and I have to ask: What are we really advocating for?

The truth is, we’re advocating for a giant scoreboard—something clear and definitive to measure our worth. Who is up? Who is down? We want the score to always tick higher, more, more, more. We want qualitative proof of recognition and connection and fame. We want to be champions.

Here’s a quote I love: “Most of us come to grief because we want too much.”

Wanting. It’s more addictive than nicotine.

Wanting emerges as a soft white fog, billowing over our thoughts. We love to rationalize it. We frame it as goal setting, as ambitious career plans, as a good reason to spend 10 hours behind a laptop. Of course you want to play the game—that’s how you win. Who doesn’t want to win?

The 1972 Permian Panthers were full of wanting: To win for their town, to earn the respect of their peers, to prove they were the best.

“You should set high goals,” the game tells us. “You should be a champion.”

But look closely: it’s just wanting.

“I have 20,000 Twitter followers.”

I want to be worthwhile.

“I write 3,000 words every night.”

I want to be understood.

“I just negotiated for 6 figures.”

I want to be valued.

“I eat organic foods, sleep eight hours a night, meditate, and optimize my work schedule.”

I want to be loved.

The game will not satisfy these wants. When you get too old, or too boring, or too careless on Twitter, the game will be over. It will leave you stranded in Odessa, Texas, alone, checking for rust on oil pumps.

We’re all in control of how much we play the game. We do not need to be champions. We do not need to watch the scoreboard. We’re allowed to walk off the field, to slam the gate of the stadium behind us. We can exchange the roar of the crowd for the quiet of a dirt field, a place to toss a ball around with a few friends—to play a game that makes us whole rather than leaves us hamstrung.

Isn’t that what we all want?

XOXO,

Ali

#TEXASFOREVER.

The book: Friday Night Lights

My rating: 🏈🏈🏈🏈🏈

Read more: An Unprecedented Look at the High-School Football Team That Inspired “Friday Night Lights”

Subscribe to Writing from Kate & Ali

Links & excerpts from two writer friends, Kate Lucky & Ali Montag.

Excellent article! I am 65 years old and used to have a sports blog with thousands of subscribers and I finally got tired and gave it up. It does get to a point where it controls your thoughts, energy and time.

Wow this is so powerful. Thank you so much Ali.