Discover more from Writing from Kate & Ali

Dear Kate,

I am writing you this letter from Alpine, Texas. Alpine is the last town to stop for gas in before reaching the empty, desert expanse of Big Bend National Park. It’s chilly here, and I’m up early. I’m eating a steaming kolache from a diner called Judy’s Bread and Breakfast. Judy sells jalapeño kolaches, hubcap-sized cinnamon rolls, any number of “Cowboy Breakfast” platters, and biscuits with gravy. I think she uses the same sweet bread dough to make all of it.

When I paid for my coffee and kolache, I asked the waitress if it’s mostly tourists and campers who eat breakfast at Judy’s. She nodded toward other patrons, a few elderly folks pouring gravy over their sausages and turning through the local newspaper, The Alpine Avalanche.

“No,” she said, smiling. “These are locals.”

Coca Cola memorabilia lines the shelves at Judy’s. One big, slow fan turns on the ceiling. A church pew doubles as a bench. Across the street from Judy’s is a bookshop with dark shelves and guide pamphlets to the Texas desert. While browsing, I hear a man joke with the owner. “You never paid me for fixing your computer last week, Sue,” he says. “The price is one whole tray of your lemon bars. And I mean a whole tray, don’t you try to sneak one out.”

The town is quiet. But it’s alive. Life goes on.

You mentioned Steve Jobs in your letter last week. In West Texas, I couldn’t be further from Palo Alto. But both your letter about Jobs and this sturdy, indefatigable town have me thinking about a long-lost value: commitment.

Jobs had a single commitment in life: to build the most beautiful products possible at the intersection of art and technology. This commitment applied to Apple, NeXT, and Pixar. It sounds lofty and big, but it was also quite focused and small. It even applied to the layout of circuit boards.

I love this anecdote from an article I wrote at CNBC in 2018:

While at the helm of Apple, Jobs insisted that every element of the Macintosh computer be beautiful, down to the circuit boards inside. When the computer was finally perfected, Jobs had the engineers’ names engraved inside each one. “Real artists sign their work,” he told them, according to [Walter Isaacson’s biography.]

“No one would ever see them, but the members of the team knew that their signatures were inside, just as they knew that the circuit board was laid out as elegantly as possible,” Isaacson wrote.

Jobs further explained to Playboy in 1985:

When you’re a carpenter making a beautiful chest of drawers, you’re not going to use a piece of plywood on the back, even though it faces the wall and nobody will ever see it. You’ll know it’s there, so you’re going to use a beautiful piece of wood on the back. For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through.

This is the opposite of shipping a “minimum viable product.” This is the opposite of “move fast and break things.” Jobs cared. He was committed to craftsmanship. Excellence. Quality. His name is on the patent for the glass staircase at Apple stores. It’s on more than 350 other patents, too.

Tech companies may retain Jobs’s management style, aesthetics, and philosophy, but the products flowing out of Palo Alto have shifted. “Growth hacking.” “Stickiness.” “Network effects.” “Hockey stick numbers.” Above all, “daily active users.”

Why not make everything a marketplace? Why buy a house when you can rent an Airbnb? Why own a car when you can take an Uber? Why lease an office when you can pop into a WeWork? Why belong to a gym when you can download Classpass? Why go to church when you can use Headspace? Democratize everything. Fractionalize everything. It’s equitable. It’s better. Even here in Alpine there is an Oyo Hotel, a short-term rental chain financed by SoftBank.

But that shift came with a consequence.

Our generation is allergic to commitment. We want flexibility. We want optionality. We want as many choices as possible. Tech is now the irritant that provokes the allergy. I can watch thousands of shows on Netflix, instantly. I can buy millions of products on Amazon, instantly. I can listen to the world’s music on Spotify, right now. I can date any man on this planet, anywhere, anytime, in my pocket. Why would I make a permanent choice about anything? Why commit at all?

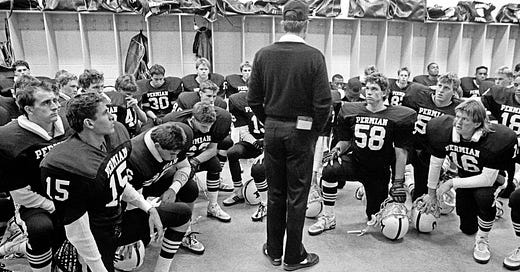

Alpine was founded in 1882. It is in a desert. It is hard to live here. This town wouldn’t exist without commitment. People here worked with their hands: on railroads. In mines. On cattle ranches. They stayed put. They bought homes and raised kids. They baked cinnamon roles morning, after morning, after morning. They remained committed.

But would any of our friends move to Alpine today? Would any of us agree to stay in one spot for ten years, much less 138?

Or would we rather bounce around from city to city, one-bedroom apartment to one-bedroom apartment, looking for promotion after promotion; matcha lattes, yoga classes, and quick bursts of satisfaction?

Choices are cheap. What we don’t acknowledge is the high cost of a life without commitment.

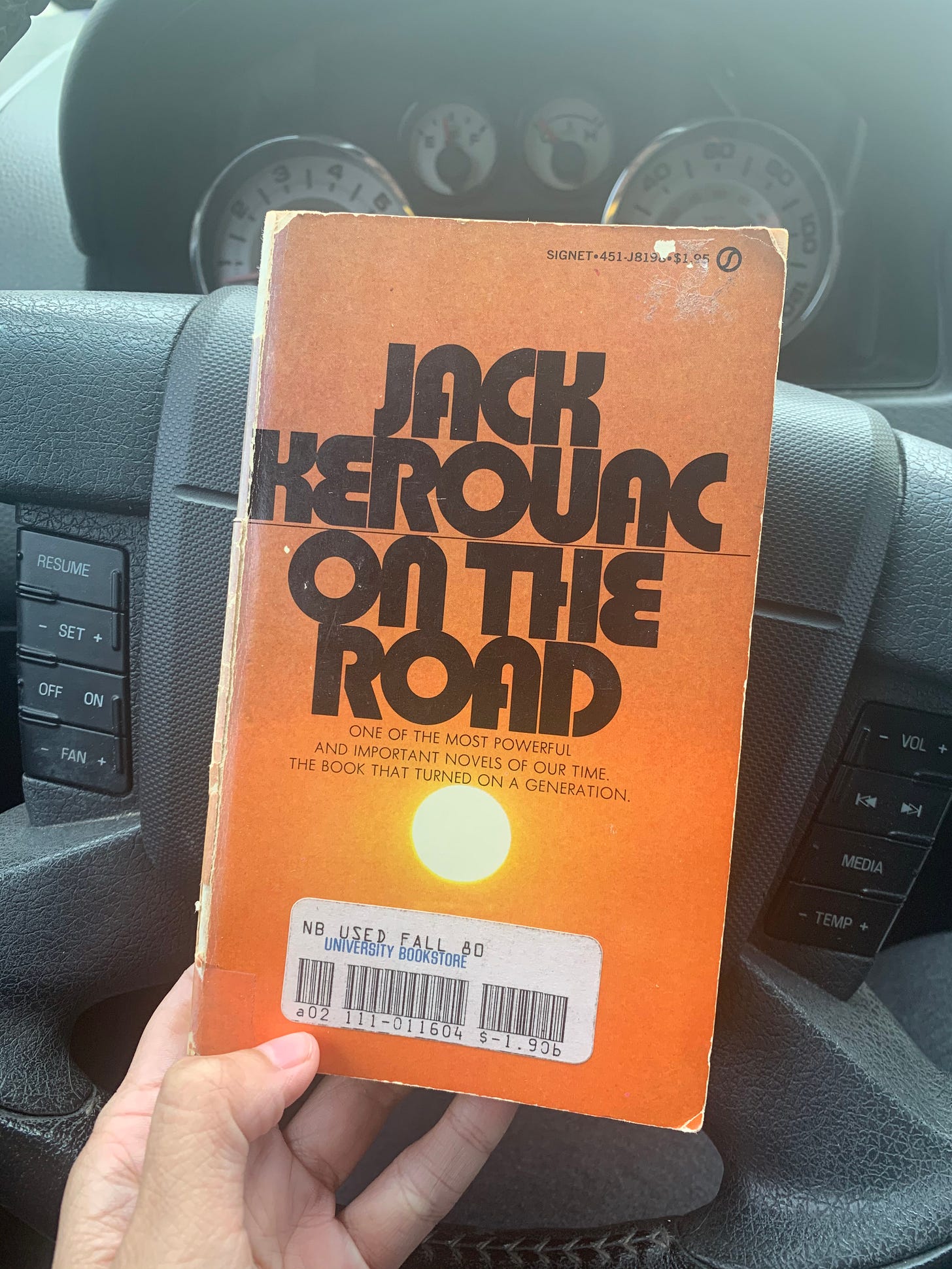

To illuminate that cost I recommend reading On The Road, by Jack Kerouac. It was a terrible book. I think it’s still worth reading.

My Book Pick: On The Road

On The Road is the seminal male adventure. Hitchhike. Drink whiskey from a paper sack. Start bar fights. Sleep on a bench. Discover yourself under the stars.

Kerouac’s character Sal Paradise hitchhikes around the U.S. with a gaggle of friends, who have sex with the women they meet and leave them the next day, drink whiskey when they can afford it, and drink beer when they can’t.

The point is to experience life, to see it, to taste it, to live with wild abandon in contrast to the stringent cultural norms of 1951 (when the book was published). Sal Paradise is a young author following Dean Moriarty, a wide-eyed, shiftless explorer that chases after all of life’s adventures.

When Sal first meets Dean, he is entranced. This passage really hits me. I have a tendency to chase the wild ones, too.

“I shambled after [him] as I’ve been doing all of my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn, or say a commonplace thing but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.”

But the book reads like an instruction manual for what not to do to have a happy life. It raises critical concerns about the cost of being “unattached,” and “free.” Kerouac's character isn’t fulfilled from his travels, but left lonely and broken. Dean Moriarty is left penniless with four children scattered across the country. In the end, Sal Paradise tells Dean Moriarty he dreams of a quiet peace. Commitment.

"I hope you'll be in New York when I get back," I told him. "I hope, Dean, that some day we'll be able to live on the same street with our families, and get old together."

The book: On The Road

My rating: 🚗 (one out of five)

Read more: The cost of the “on demand world.”

XOXOX,

Ali

Subscribe to Writing from Kate & Ali

Links & excerpts from two writer friends, Kate Lucky & Ali Montag.